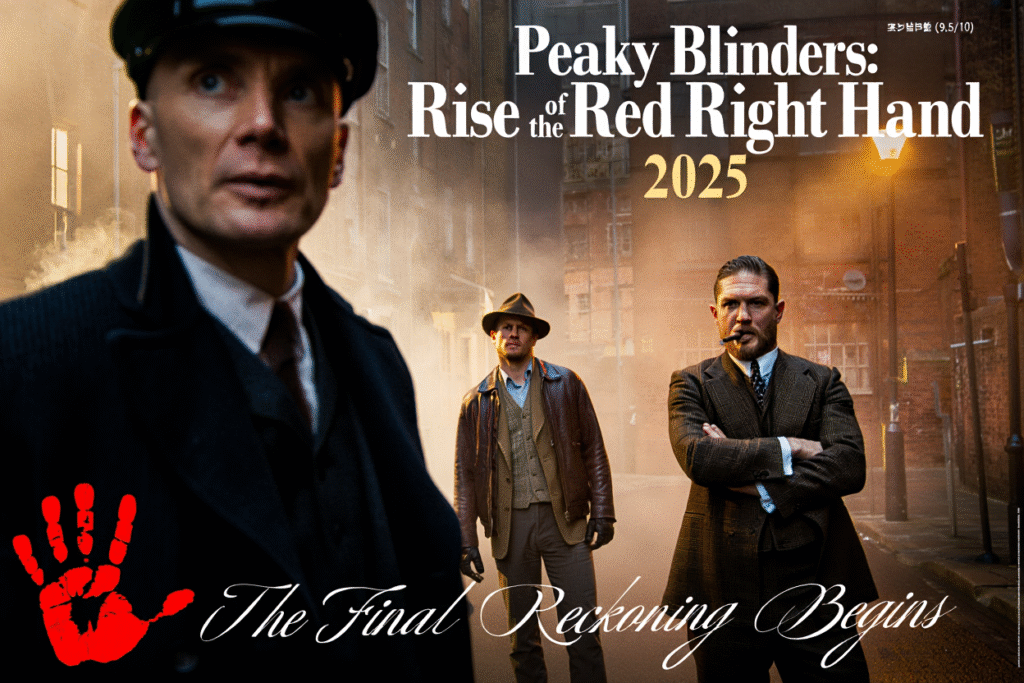

It ends not with a whisper, but with gunfire, whiskey, and whispered prayers to gods long forgotten. Peaky Blinders: Rise of the Red Right Hand (2025) is the long-awaited, blood-soaked conclusion to one of television’s most iconic sagas — a farewell as haunting as it is electrifying. Cillian Murphy returns as Thomas Shelby for one final reckoning, a man burdened by ghosts, sharpened by time, and finally ready to face the devil in his own reflection.

Set in 1936, as fascism tightens its grip across Europe, the once-unbreakable Shelby empire begins to crumble under the weight of its sins. Birmingham is no longer a kingdom of men like Tommy — it’s a battlefield of ideologies, where loyalty and blood mean less than politics and power. But Tommy Shelby has never bowed to kings or causes. His war, as ever, is personal.

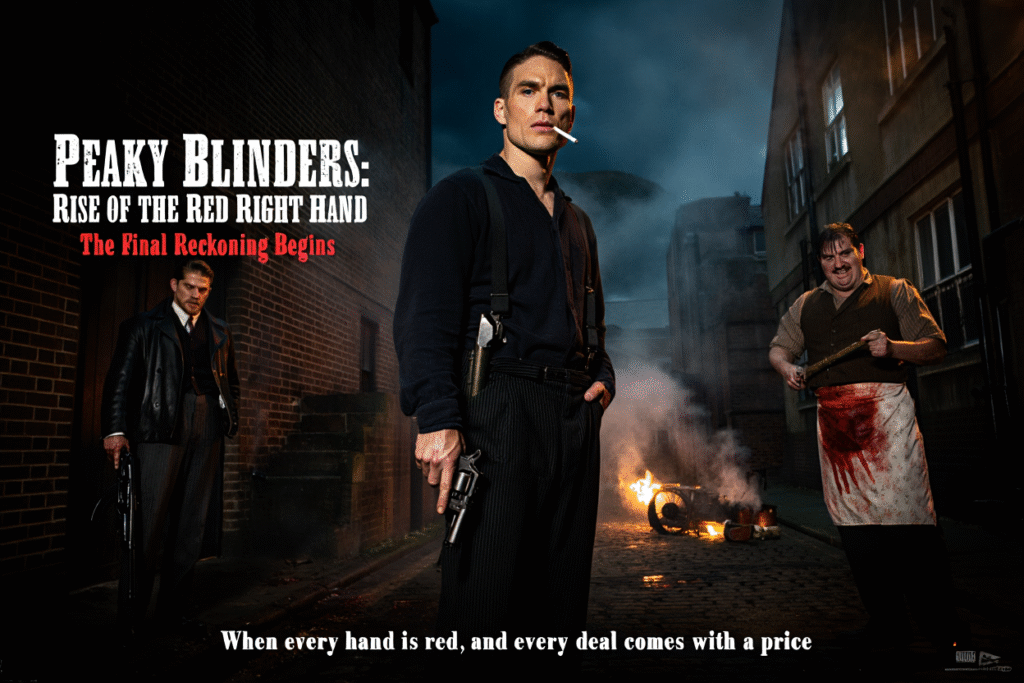

From its first frame, director Steven Knight’s feature-length finale feels like an elegy in motion — grimly beautiful, steeped in cigarette smoke and sorrow. The cinematography paints Birmingham as both tomb and throne, its factories glowing like furnaces of damnation. Rain falls constantly, as if the heavens themselves mourn what’s to come. Into this chaos steps Charlie Hunnam’s enigmatic antagonist — an American exile with Shelby blood in his veins and vengeance in his heart. His arrival reignites old wars and unearths darker truths, forcing Tommy to face the ghosts he’s spent years outdrinking.

Cillian Murphy is once again mesmerizing — all blue-eyed despair and quiet fury. His Tommy Shelby moves like a man walking through his own purgatory, each step heavy with memory. Murphy’s performance here transcends acting; it’s operatic, haunted, and heartbreakingly human. He embodies a man too clever to die and too cursed to live. The scenes where Tommy wrestles with his own mind — hallucinations, whispered voices, flashes of Grace’s face — remind us why he’s one of the greatest characters of modern television.

Charlie Hunnam, in his most commanding performance to date, plays Arthur Boyd — a former ally turned crime lord forged in the chaos of New York’s underworld. Hunnam’s Boyd is magnetic: charming one moment, monstrous the next. His connection to Tommy runs deep, tied by blood and betrayal, and when they finally meet — in a candlelit church where both men confess their sins to no one — the tension is electric. It’s less a showdown than a confession, two devils realizing there’s no redemption left between them.

Tom Hardy’s return as Alfie Solomons is the film’s beating pulse of chaos. Equal parts philosopher and madman, Alfie provides grim humor and biting wisdom in equal measure. His dialogue crackles with the poetry of menace — each word a sermon delivered from the edge of insanity. His alliance with Tommy is as fragile as ever, bound by mutual understanding that monsters recognize their own. Their shared scenes, laced with dark wit and affection, feel like a farewell to the strange brotherhood that defined the series.

The script, written by Steven Knight, is Shakespearean in scope — not just a crime story, but a meditation on power, guilt, and destiny. Every line carries weight, every silence echoes. The film’s pacing burns slow and deliberate, building tension like a fuse winding toward explosion. When violence comes — and it does, in ferocious bursts — it’s filmed not for spectacle, but for consequence. Each gunshot lands like a final heartbeat.

Visually, Rise of the Red Right Hand is stunning. The film blends industrial decay with painterly composition — smoke, rain, and fire merging into something mythic. The sound design hums with tension: distant trains, ticking clocks, and the low growl of Nick Cave’s title theme, reimagined here as a requiem. The final musical cue, a haunting rendition of “Red Right Hand” sung a cappella, chills to the bone.

But beneath the grime and gunpowder, this finale is about legacy — the cost of building an empire on blood and ambition. Tommy’s final arc strips away the myth to reveal the man beneath the razor cap: a son, a father, a soldier who never left the trenches. His last conversation with Ada — quiet, weary, filled with unsaid love — is perhaps the most devastating moment in the film.

As the story races toward its inevitable end, Tommy faces his greatest enemy: himself. In the ashes of betrayal and the silence after war, he must choose whether to die as a legend or live as a man who’s finally laid his weapons down. The ending, hauntingly poetic and open to interpretation, cements Peaky Blinders as not just a gangster saga, but a timeless tragedy — one that dares to find grace amid the grime.

When the smoke clears, and the last cigarette burns out in the rain, one truth remains: every empire ends, but some names never fade. Thomas Shelby. Spoken softly, like a curse and a prayer.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings